If someone were to ask me what is my favorite play (not musical), I will always pick Thornton Wilder’s Pulitzer Prize winning Our Town no matter how many plays I see. Even when I stop to really consider the options, I end up with Our Town. Every time I see it, whether professional or amateur, it never fails to move me deeply. Wilder’s play about small town life in the early 20th Century is not only a perfect piece of theatre, but it captures the American spirit and as the narrator of the play, “The Stage Manager,” says, “So––people a thousand years from now––this is the way we were: in our growing up and in our marrying and in our living and in our dying.” This statement, made after the main characters are introduced, points out the purpose of the play and it has held true all these years––proving the play to be timeless. Clearly it was Wilder’s plan that his play should capture the American experience, which has something to do with the simple things in life as they are found in the microcosm of America that is the small town and the goings on along its Main Street. The simple things can also be the biggest things in the course of a life.

Although the play might seem like it is now a big nosalgia trip, it was written as a bit of nostalgia in the first place––it is set in that time right before everything started going very fast, before the Great War, before cars and radio and movies. Walt Disney loved to explore this time in many projects, for it was that very time when we was a boy. Lady and the Tramp might be about the love affair of two dogs from two different social classes, but the world in which that story is told is a time when horse drawn buggies and automobiles were trying to figure out how to share the road. This is an interesting period, for it represents one of the big themes of Our Town: the old giving way to the new––one foot in the past and one foot in the future. The play celebrates the period as well as mourns its loss and the period seems a perfect metaphore for the American experience. In 1938 when the play ran on Broadway at the Henry Miller Theater (rebuilt and renamed “The Sondheim” today), the time depicted in Our Town’s Grover’s Corners was in the memory of most of the adults going to see the show––they were looking at their own childhoods. A ten year old being taken to see Our Town in 1938 wouldn’t have any personal point of reference to 1901, for they had radio, comic books, cars, phones in their homes, Mickey Mouse and Snow White in color at the movies. Today we are also like those ten year olds of 1938, for we have no personal connection to that time before the world became very turbulant, but whether or not you grew up in a small town, the basics of humanity depicted in that play are universal forever and we can relate to those things that are eternal.

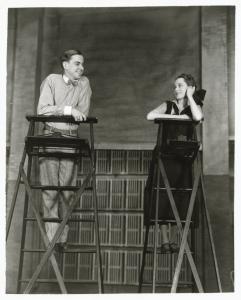

From a physical production standpoint, Our Town really knows it is a creature of the theatre. In this period of American Theatre, kitchen sink realism was all the rage, but Wilder asks the audience to use their imagination. On a basically bare stage he has his “Stage Manager” explain to the audience that they won’t need scenery and just a few chairs, tables and a pair of ladders will serve. The cast is usually costumed in the period, but past a useful lighting design and a bit of music, this is all there is or needs to be for production value––the actors do all the work. Most of the activities are pantomimed, from sipping an ice cream soda, to making breakfast on the stove. The real meat of the play is in the conversations between the characters of the town––how they say hello in the street, talk about the latest news or gossip and share schoolwork, sentiments and dreams.

One of the aspects of this play that always moves me (differently from production to production), is hearing about the characters’ dreams, many of which are not fullfilled. Mrs. Gibbs wants more than ever to go to Paris one day, but her husband won’t hear of it. She mentions that a man has called on her to buy her antique piece of furnature for $350 (that’s 1901 dollars folks), which would pay for a trip to see Paris. Mrs. Webb encourages her to sell the furniture piece and to just keep dropping hints to Mr. Gibbs so that sooner or later he’ll break down and they’ll take the trip. High schooler George Gibbs wants to go to college and study agriculture. High schooler Emily Webb plans to get married to George Gibbs and have a family. These dreams are all curtailed or compromised. They are filled in with other turns of fate that lead the characters down different paths. Mrs. Gibbs never sees Paris, but we find out that she leaves the money to her daughter and son-in-law and they use it to help modernize their farm. George, worried that going away to college will end his romance with Emily, stays in Grover’s Corners to take over his uncle’s farm and marry Emily. Emily does get married, but dies giving birth to her second child, leaving George alone to raise their four year old son, so her dream was short lived.

Little Joe Crowell, Jr. the paperboy, has the cute line in reaction to the news that his teacher is getting married and leaving her profession, “I think if a person starts out to be a teacher, she ought to stay one.” The Stage Manager fills us in on a lot of Joe’s history and although we don’t see anymore of him after his one scene we learn of his dreams too. I am always moved by his story and it is the first of the dashed dreams in the play. Little Joe had graduated top of his class and went to college to become an engineer, “But the war broke out and he died in France. All that education for nothing.” That line kills me. The Stage Manager finishes, “Of course, what business he had picking a quarel with the Germans we can’t make out to this day. But, it did seem perfectly clear at the time.”

Joe’s story is so simply told, but you see this little boy delivering papers, he has a few lines with the town doctor about his teacher getting married, and then we’re told he was one of the most promising kids from Gover’s Corners. Just as he’s about to start his adult life he is killed in the war. Over. This idea, potent anytime, has seemed all the more potent to me in the last two New York productions taking place during a time when we hear in the news all the time about our current soldiers parishing as they fight for their country. And that last bit really resonates: “...it did seem perfectly clear at the time.” Take one soldier out of the crowd and really look at who he is as an individual and you can’t begin to understand why his death is justified.

Another war related piece of history is told to us in the third act as the Stage Manager wanders around the cemetary and stops in the Civil War area. He says they were, “New Hampshire boys...had a notion the Union ought to be kept together, though they’d never seen more than fifty miles of it themselves. All they knew was the name, friends––the United States of America. The United States of America. And they went and died about it.”

Reading the text that repeats “The United States of America” a second time doesn’t alone register as particularly moving, but in the hands of Paul Newman on Broadway in 2002, with his aged voice speaking so soothingly throughout the production, he suddenly became very strong and sure of voice, underlining with his tone that second “United” of the sentence. He half said it to himself and half threw it out to the audience by punching the air in a gesture of perseverance. Then he sorrowfully turned to the audience to state, “And they went and died about it.”

Partially it was Paul Newman standing before me (I was in the first row). Partially it was his excellent line reading, which came from a man who had known the wars of the 20th Century, but it was also Wilder’s observation about the boys who fought in the Civil War––fighting for a huge country of which they couldn’t have seen more than fifty miles. That’s astounding when you ponder it and it’s not unlike our soldiers shipping out to the south seas or Europe or the Middle East.

The 2002 Broadway production was particularly moving during the wedding scene––and here we get that wonderful way that the audience can really be brought into the play: Emily actually came down the theater aisle from the back of the house as the organ played the march from Lohengrin. We all turned to look at her, just as we all do at actual weddings, and that notion of the event suddenly becoming so real as life––that we were right in the play along with the characters––was more moving to me than an actual wedding. I suppose, too, this was one of the strongest of many moments in Our Town where you realize how much is the same from generation to generation regardless of progress and all the changes you can name.

In a 2009 Off Broadway production directed by David Cromer (who also played the Stage Manager), the choice was to costume the actors in modern dress and read the lines with as contemporary a delivery as could be managed without rewriting. The disconnect to the 1901 period becomes too jarring with this choice. To see the teens acting so reserved, polite and bashful while dressed in modern clothes and plugged in to ipods just doesn’t read as believeable. Also, it is the beauty of the play that we see ourselves in characters living a century ago. We don’t need modern dress to drive the point home. Our Town has a big cast and in a small Off Broadway house it must have been pretty tough to get top acting talent to agree to what has to be a horrible contract. That production was critically acclaimed and ran a long time, but the quality of the acting wasn’t there in all cases. The George and Emily were particularly weak, which is a big problem as they carry the greatest emotional weight of the play.

So, if the acting was poor, what was it that delighted the critics? This production had a big directorial trick dropped on the final sequence, which paid off the modern dress choice beautifully, but at the expense of a stellar performance from Emily and confusion caused by the clash of periods. The director had Emily going back for her one last day on earth, usually fullfilled by Emily’s words and the audience’s imagination, to find a realistic turn of the century kitchen with Mrs. Webb cooking actual bacon in period dress. Now the period was realized, but in every possible detail and it was something to actually smell that bacon frying and coffee brewing. This scene was such a surprise after having no scenery and no costumes and did drive home Emily’s line, “Oh earth, you’re too wonderful for anyone to realize you.” The concept was perfectly suited to the ideas of the play, but the rest of the play up to that point was compromised––somehow that elaborate final scene was so overpowering that you could forgive or forget how second rate the rest had been. However, with a good Emily, as was Maggie Lacey in the 2002 Broadway production, you didn’t need anything more than the actress and Wilder’s words to evoke the emotions from the “Good-bye World” speach in that final scene.

The other thing that worked in that Off Broadway production, in the end, was that the play is strong enough to survive less than wonderful key players and you realize rather quickly that you are watching an American treasure and the poetry of the piece emerges regardless of a bland line reading. Some of the lines I find most endearing include:

“The morning star always gets wonderful bright the minute before it has to go...doesn’t it?"

“I’d rather have my children healthy than bright.”

“Both of those ladies cooked three meals a day––one of ‘em for twenty eyars, the other for forty––and no summer vacation. They brought up two children apiece, washed, cleaned the house––and never had a nervous breakdown.”

“A man looks pretty small at a wedding, George. All those good women standing shoulder to shoulder making sure that the knot’s tied in a mighty public way.”

“Everybody locks their doors now at night. Ain’t been any burglars in town yet, but everybody’s heard about ‘em.”

"Wherever you come near the human race, there’s layers and layers of nonsense....”

“Do human beings ever realize life while they live it?” asks Emily. The Stage Manager answers, “No. The saints and poets, maybe––they do some.” That is Wilder’s reminder to stop and smell the roses and for a few more minutes, before we exit the theater and go back to our turbulant world, we think that we really should stop to appreciate the little things that make up a life. There is a sadness in the swift realization that we will take much for granted just as before we saw the play, for it is in our nature. However, when we stop for a few hours to see a play––any play––we are stopping to pay attention to humanity. Our Town in particular, illuminates the beauty of humanity.

You can see the original Stage Manager, Frank Craven, in a 1940 film version with a young William Holden as George. Hal Holbrook can be seen as the Stage Manager in a 1977 TV production. The 2002 Broadway production was filmed for television and is available on DVD, though it wasn’t recorded before a live audience, which diminishes the energy to a degree. It’s still worth a look. A documentary called, OT: Our Town, shows an English teacher working in a Compton, CA school struggling to put on a production of Our Town––the first production of a play in twenty years. The final result is magical, not only because the kids connect to the play, but their parents seem to be genuinely moved by the theatrical experience and the act of putting on the play brings a sense of community to a community that is very splintered.

Of the original production, Brooks Atkinson said in the New York Times that, “Our Town is one of the finest achievements of the current stage.” If someone were to ask me, what did I think was the greatest American play, I would find it difficult to pick one, but if I have to pick only one I pick Our Town.

John Craven and Martha Scott in Our Town. (1938)

No comments:

Post a Comment